Mike Pompeo’s ‘democratic plan’ for Venezuela and Juan Guaidó’s alleged involvement in terrorist regime change operations

After bizarrely placing Nicolás Maduro top of a wanted list on charges of drug trafficking, the Trump administration then unveiled a so-called ‘democratic transition plan’ that calls for the ouster of the Venezuelan President in exchange for a five-person “Council of State”.

Irrespective of the hardships already suffered by the people of Venezuela under the current sanctions programme, and heedless to a worsening situation due to the coronavirus pandemic, the US is threatening “increased” sanctions if Venezuela does not comply.

Yesterday, Aaron Maté from The Grayzone spoke to Latin America policy analyst and campaigner with Codepink, Leonardo Flores, about the latest US effort to starve Venezuelans into submission in order to force a regime change.

Towards the end of the interview, Leonardo Flores describes the extraordinary revelations of Cliver Alcalá, who is one of those indicted by the US Department of Justice on accusations of narco-trafficking. Shortly after the DOJ press conference ended, Alcalá actually confessed on Twitter that he was involved in plots including terrorist attacks to overthrow Maduro.

Additionally, he said weapons confiscated by Colombian police were paid for with money provided by Juan Guaidó. However, Alcalá was not only implicating Washington’s choice for Venezuelan President, Juan Guaidó, scandalously seen photographed with members of the infamous Los Rastrojos drug cartel, but also an unspecified number of US advisors, who he claims met with him on no less than seven different occasions. Alcalá has now been turned over to US authorities.

The transcript of the interview below is mine [interview begins at 1:50 mins].

Aaron Maté: What is your reaction to this so-called ‘democratic transition plan’ from Pompeo?

Leonardo Flores: My reaction really is bewilderment. Because a few days ago, as you just said, the Department of Justice unveiled indictments against Maduro and 13 other former and current government officials and members of the military; immediately ramping up the pressure. And then this transition proposal seems to be kind of a step back.

First of all it’s a total non-starter. It’s not going to go anywhere. It wasn’t negotiated with anyone in Venezuela on the side of the government. It’s a plan that supposedly came from Juan Guaidó in part, but really it’s been designed in the State Department itself.

AM: The thinking here in the White House, what do you think it is? They’ve been trying now for more than a year to overthrow Maduro. They’ve tried to spark some military uprisings. It hasn’t worked. Now they’ve shifted to this bounty last week on Maduro’s head. Wat do you think is the strategy going on inside Washington? What are they hoping to achieve with these narco charges against Maduro, and now this new so-called plan?

LF: Well, in a sense they’re just trying to throw everything at the wall to just see what sticks. But, particularly with this plan, I think it’s to alleviate the pressure that’s coming on them due to the sanctions.

We’ve seen everyone from the UN to the EU to other multilateral organisations and NGOs call for a lifting of the sanctions. We’re seeing a letter being sent around the Senate that has at least 11 people who’ve signed on led by Senator Chris Murphy calling for humanitarian relief for Venezuela and Iran: lifting the sanctions during this pandemic. And so I think that’s maybe getting to the Trump administration and this is their way of sending some kind of olive branch to these more moderate factions in Washington. But, you know, it’s not a serious proposal.

Side note: “It hurts our nation’s security and our moral standing in the world when our sanctions policy results in innocent people dying. I am particularly concerned about the impact of sanctions on the COVID-19 response in Iran and Venezuela”

— Sen. Chris Murphy

AM: What I think has been overlooked in the discussion of all this is that in trying to install Guaidó, the Trump administration has portrayed this picture where it has been basically Maduro versus Guaidó, and there’s no-one in between. But meanwhile, there have been negotiations between Maduro and elements of the Venezuelan opposition, just not the one that includes Guaidó’s faction. Can you talk about this and how it’s been ignored.

LF: Sure. So, the last time Guaidó participated in negotiations seriously – his faction I mean – was in August 2019. And those talks were undermined when the Trump administration imposed what the Wall Street Journal called an economic embargo; they really ramped up the sanctions on August 5th.

After that, about a month later, Nicolás Maduro and the Venezuelan government began negotiating with more moderate sectors of the political opposition – sectors of that really want to engage in democracy and engage in politics and aren’t looking for regime change. And coincidentally, those months of 2019, I’m talking about September, October and November; they were the most stable months in a really crazy year for Venezuela, that started off with this attempted coup by the Trump administration and Juan Guaidó.

Now, those negotiations are still ongoing. There’s ongoing dialogue. They resulted with – in early January – with a new election for the President of the National Assembly. This new President of the National Assembly was from the same party as Juan Guaidó. I think he was expelled from that party – but I’d have to check up on that to be honest. And what we’re seeing is that Juan Guaidó got kind of pushed out and these extremist opposition sectors got pushed out a bit from these attempted negotiations. So this is their way back in, so to speak.

AM: So, if you could address someone who might look at this plan now from Pompeo and – the way Pompeo’s framing it is that, you know, the US has no preference for who leads Venezuela aside from Maduro. We want him gone. In fact, Pompeo said as much today. Let me play you a clip…

Mike Pompeo: We’ve made clear all along that Nicolás Maduro will never again govern Venezuela, and that hasn’t changed.

AM: That’s Mike Pompeo. Well first of all, let me just ask you to respond to Mike Pompeo, the Secretary of State of the United States, declaring that the leader of another country will never govern there again.

LF: I mean it’s completely ridiculous. Maduro has been governing since 2013 and he has been governing throughout this whole time when the State Department has been trying to portray Venezuelan government as nonexistent and they’re trying to force Juan Guaidó as the so-called “interim president”.

But what’s really curious to me is that there’s contradictions within the White House. So that’s a very interesting Pompeo quote, but earlier today, Elliot Abrams, who’s the Special Representative for Venezuela for the Trump administration; he told Reuters that “while Maduro would have to step aside” – and this is a direct quote [the plan did not call for him to be forced into exile ] – “the plan did not call for him to be forced into exile and he even suggested that he ‘could theoretically’ run in the election.

So Abrams is saying ‘hey maybe Maduro can run’, Pompeo’s saying ‘Maduro is never again going to be able to govern’. There’s clear disconnect. It’s kind of indicative of what we’ve seen in the White House since Trump to office, with lack of communication between different sectors of the executive branch.

AM: Let’s say that Abrams, what he suggests, is the proposal that the US is putting forward, then somebody might look at that and say, hey you know listen the US shouldn’t be involved in Venezuela, but it is, and the fact is that right now they’re putting forward this plan where they’re offering to relieve these crippling, murderous sanctions if Venezuela just agrees to this new transition and hold new elections. Why not just abide by that to help ease the suffering of Venezuela?

LF: Well, Venezuela has a constitution. I mean that’s the biggest thing we have to talk about. It is a sovereign country that has a constitution, and is guided by that constitution. And so the Trump administration used that constitution, and made these kind of quasi-legal arguments, to say that Juan Guaidó was actually the real President because Maduro was ‘not officially in power’. And now they’re turning around and saying well you know what, forget that constitution and let’s talk about this whole ‘democratic framework transition’ that has no constitutional basis in Venezuela at all.

But what I think we really need to emphasis is that if the Venezuelan government decided to hold new elections – new presidential elections – after coming to an agreement with the opposition, they’re well within their rights. But this plan is being imposed from abroad, it lacks any sort of popular support within Venezuela, and in that regard it’s a non-starter.

AM: Just to stress this point, I do think holding new elections – that has been under discussion in Maduro’s negotiations with the opposition, right?

LF: Yeah, that’s correct. I mean first of all there have to be new elections – I mean parliamentary elections because those are due this year. And after those parliamentary elections there is the possibility that you might have new presidential elections in Venezuela.

But there’s no way that those presidential elections can be carried out while Venezuela is under sanctions from the US and the EU; particularly by the US sanctions. This is reminiscent of Nicaragua in the ’90s when the Nicaraguan people had an election and the US government said that if the FSLN [Sandinista National Liberation Front] then wins, then the sanctions will continue, but if the opposition wins then the sanctions will be lifted.

AM: Let me play for you a clip on that front. This is John Stockwell, he is a former CIA officer, and he was describing this tactic the US uses of basically making countries like Nicaragua submit to US demands or starve.

John Stockwell [speaking on December 27th 1989]: The point is to put pressure on the targeted government by ripping apart the social and economic fabric of the country. Now that’s words, you know, social and economic fabric: that means making the people suffer as much as you can until the country plunges into chaos, until at some point you can step in and impose your choice of governments on that country.

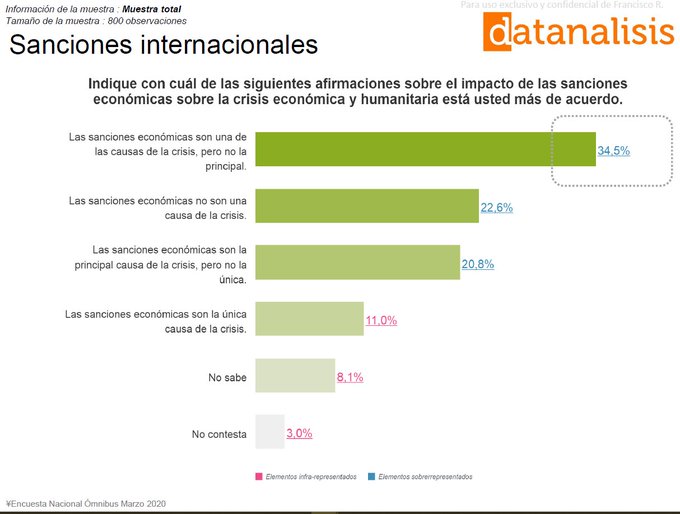

AM: So that’s a former CIA officer describing the US approach to countries like Nicaragua and Venezuela. Leo, what’s your sense of where the Venezuelan people are at? They’ve been suffering for a long time now under these sanctions. There was just a poll that was shared by the opposition economist Francisco Rodríguez pointing out that two-thirds of Venezuelans say that US sanctions are causing huge misery inside their country.

What is your sense of where the electorate is at inside Venezuela? The people: are they at the point where they’re willing to give up [and] to submit to US demands, whatever they are, in return for some relief from this blockade?

LF: No, I wouldn’t say they are. I mean we have to be clear though, Venezuela is a very polarised country. So we have this sector that votes for the opposition – that a good percentage of it would likely welcome Pompeo’s plan. But then you have the Chavistas, which represent at least 40% of the electorate, and of all eligible voters, and they would absolutely reject this plan.

It’s absolutely true though that sanctions have completely destroyed the economic fabric of Venezuela. But one of the reasons that Venezuela has been able to overcome the pressure from the United States is due to the social fabric, and due to the organising at the community level, and due to the organising that the government enables from above.

AM: Okay, so you mentioned the Venezuelan electorate. Let me ask you quickly about this, because a huge talking point that the US administration uses and its parroted across the political establishment – even Democrats who oppose the sanctions parrot this talking point –which is that Maduro is not a legitimately elected leader, and they point to alleged fraud in the 2019 Venezuelan elections.

I know it’s complicated but can you give us the simplest case for why this talking point is false.

LF: Right. So, there’s actually no evidence that there was fraud, and really the argument that there was fraud only comes from the United States.

What happened in the 2018 elections is that sectors of the opposition just decided to boycott the election. And they boycotted at the direction, or under the instructions of the State Department.

In early 2018 there was dialogue between the government and the opposition. The two sides were very close to signing an agreement – they actually had an agreement written down. They were negotiating in the Dominican Republic, they went back to Venezuela for one week to consult with various parties involved; during that interim week, then-Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, threatened an oil embargo, and he also suggested that if the military were to overthrow Maduro, that this move would be welcomed by the United States.

Also during that week, the State Department said that they would not recognise any elections in 2018: that Maduro had to go first before there were elections. That’s what leads to these kind of claims of fraud because of this opposition boycott. But really there was no fraud: the parties that did participate, participated fully; there were international observers; there was a vote that was audited; and Maduro won in a landslide election.

AM: Maduro received over six millions votes, and, if I have the history correct, the main opposition candidate, Henri Falcón, who ran, he was even threatened with US sanctions if he kept participating in the elections.

LF: That’s right. And not only was Henri Falcón threatened with sanctions, but so was Allup who was leader of Acción Democrática – Democratic Action Party – this is one of the bigger opposition parties. It’s slightly more moderate than Juan Guaidó’s party. But he said, I think it was in March of 2019, excuse me 2018, he pondered ‘why would I run, if the US isn’t going to recognise my victory?’

And so the US made it clear that even if an opposition leader had won, that they were not going to recognise it because it wasn’t going to be the opposition leader that they wanted.

AM: So let me ask you about these narco-trafficking charges that have been unveiled against Maduro and other top officials. The allegation – and maybe you can explain it for us – because it’s pretty bewildering: is that Maduro and the other top Venezuelan officials have been engaged in a criminal conspiracy to flood the US with drugs, going back many years.

LF: Yeah, that’s correct. And so the DOJ talks about a plan to plot to flood the US with cocaine since 1999. Maduro wasn’t even in power in 1999. In 1999, he was a member of the National Constituent Assembly and he was helping to draft Venezuela’s constitution.

So one of the interpretations of these accusations in Venezuela is that these aren’t accusations against individuals, it’s really an accusation against the entire Bolivarian revolution. And going a little bit deeper, this plot claim by the DOJ is patently ridiculous, I mean, the US government’s own statistics show that over 90% of the cocaine in the United States is either from Colombia, or has travelled through Colombia. Those same statistics show that less than 7% of the cocaine that the United States has transited through Venezuela at some point.

Venezuela doesn’t produce coca – the coca leaf – it doesn’t produce cocaine, whereas Colombia is the biggest producer of both coca and cocaine in the entire world. It’s clear that these accusations – these charges – are completely politically motivated and they’re not based on any sort of reality.

If they were, then really the conspiracy to flood the United States with cocaine – you have to look at the President of Colombia and the prior President Álvaro Uribe and really the kind of entire Colombian social structure, which enables narco-paramilitaries to control their society and to support cocaine.

AM: And you’ve written about, for The Grayzone, a piece that explains that one consequence of this indictment, is that it’s triggered a confession – a very serious confession – by one of the people charged of a violent US-based plot against Maduro. Can you explain what happened there?

LF: Right. So one of the people indicted, his name is Cliver Alcalá, he was a former member of the military. He used to be very close to Chavismo. He flipped to the opposition in 2016 and since 2017, give or take, he’s been involved in various plots and coup attempts [including] attempted terror plots in Venezuela. He’s been linked to them.

And so immediately after the DOJ press conference last week that indicted Mr Alcalá, he posted some videos on Twitter and other social media confessing to a terror plot in Venezuela from about a week and a half ago —

So a bit of back story: the Colombian police seized 26 high-powered rifles and several other weapons of war and military equipment. Alcalá claimed that the weapons were his – that they were bought using money from Juan Guaidó. That he and Juan Guaidó had entered into a contract for the weapons. That the weapons were going to be used to help overthrow the Venezuelan government by causing a terror plot and by targeted assassination of Chavista leaders.

Alcalá now has been turned over to US authorities. It’s unclear what’s going to happen with him, but what is clear is that he implicated not just Juan Guaidó in this terror plot, but US advisors – he claims that he met with US advisors on at least seven different occasions.

AM: And just to put a final point on this, he says that Guaidó paid him money for this plot. And so those weapons that were seized in Colombia were paid for by Guaidó, and then presumably the US which backs up Guaidó, and is actually using money initially intended for Central American aid to pay for Guaidó and his fellow coup-plotters.

LF: Yeah, that’s right. The money wasn’t necessarily going to Alcalá directly, it was going to the weapons that Alcalá purchased. And Juan Guaidó’s only source of financing is the US government, which basically is us US taxpayers.

AM: So finally, as part of its coup effort in Venezuela, the US has been putting heavy pressure on anybody engaged in business with Venezuela, and that’s included sanctioning Russia’s state oil company, Rosnef.

Rosnef was recently forced to basically divest its holdings in Venezuela and then transfer it to another Russian government – in fact, the wholly Russian government owned company. Will this be enough to keep Venezuela afloat, or do you think that the power of the US is just too strong here?

LF: I think it would be enough under slightly different circumstances, but the fact is that oil is plummeting right now and so it’s unclear what’s happening with Venezuelan government’s finances.

I don’t think the Venezuelan government is going to fall due to financing. I think in that sense, you know, China and Russia have a lot invested in Venezuela, and Venezuela has other means of securing financing, whether it’s through gold or rare earth minerals. But it does make the situation much more difficult and it has led to gasoline shortages recently in Venezuela.

AM: And finally, in terms of what can be done here in the US, you mentioned that there’s now increased talk from Congress – increased pushback from Congress – asking them not to suspend the sanctions entirely, but to simply pause them during the coronavirus pandemic, which I suppose is better than nothing.

But as we are dealing now with economic troubles of our own here at home, what do you think can be done right now to push back on the Trump administration’s coup effort, and to try to stop the regime change plot on Venezuela – and to drop the sanctions?

LF: Well, I think for starters the issue of Venezuela has become incredibly toxic in mainstream politics. So if you take any sort of position that is deemed friendly to the Venezuelan government, even if it’s actually not necessarily friendly to the government, like say humanitarian relief and [lifting] sanctions, you’re immediately going to be seen with mistrust by a certain element of the political establishment.

And so I think that really what’s most important is that to highlight what the Trump administration has been doing to sabotage dialogue in Venezuela. If it were not for Trump, I think we would already have a political agreement in Venezuela and the country would be much more stable. But he’s in thrall to his financers in Florida, the Cuban-American lobby in Florida and rich Venezuelans in Florida; it all boils down to Florida unfortunately.

I think really that the best hope that the Venezuelan government has is to hold out until after the November elections. Even if Trump is re-elected I think it opens up a possibility of negotiations between the Trump administration and the Maduro government.

AM: Yeah, on that front it doesn’t inspire confidence that Joe Biden has fully embraced Trump’s coup attempt, and has recognised Juan Guaidó as the President, but certainly, no matter what happens, November will be a key date in all this and other issues of course.

Leo Flores, Latin American policy expert and campaigner with Codepink, thanks very much.

LF: Thank you Aaron.